What are we talking about?

Four abstractions removed from reality

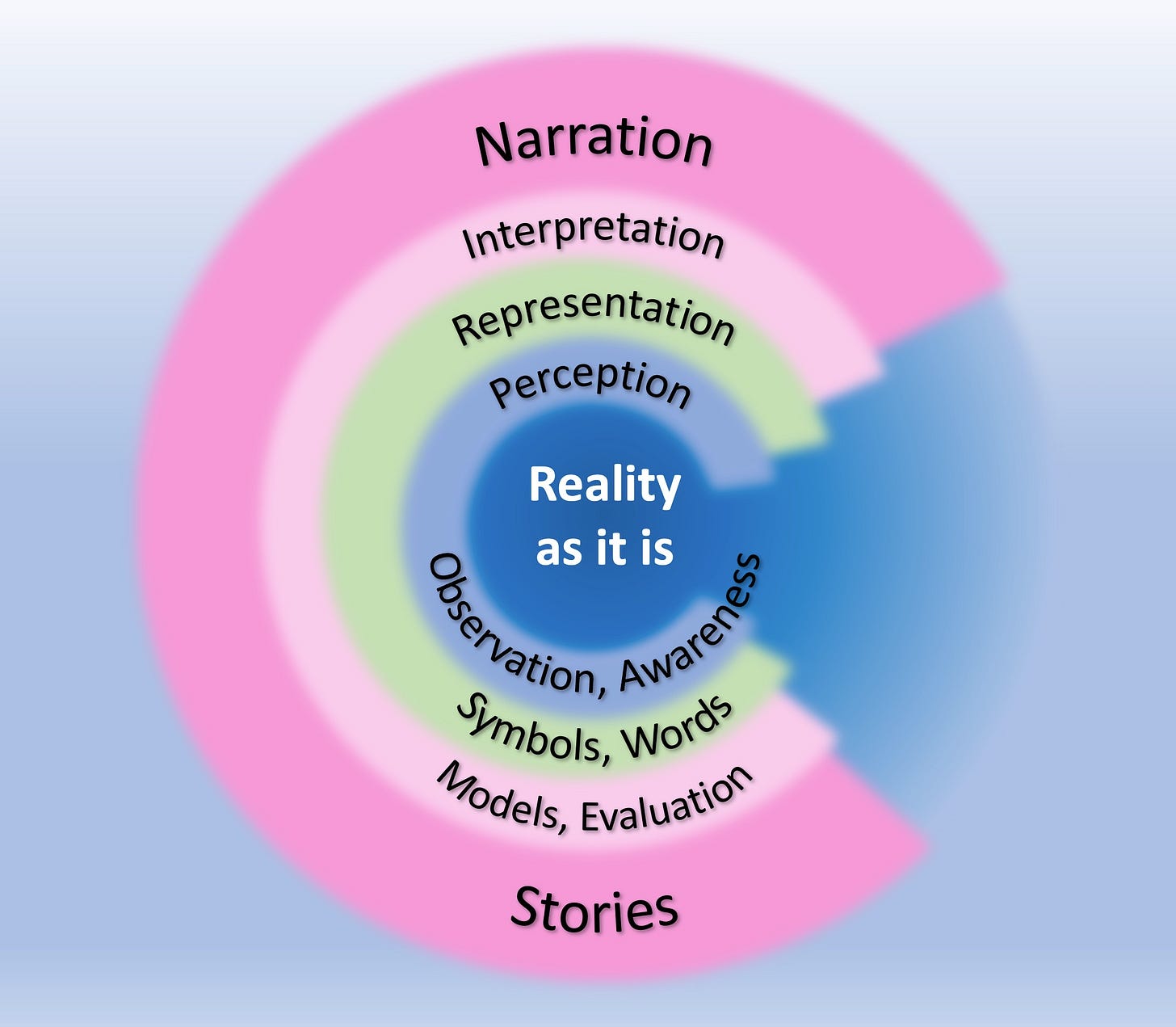

Although we all live in the same world and share a single reality, we often seem to be worlds apart when discussing important issues. What is going on? Reality is vast, complex, and dynamic. Humans have only investigated a small portion of the universe, and our investigation is incomplete. Our perceptions of reality are neither complete nor accurate representations of reality. We do not observe the many cosmic rays passing through us each second, the atoms that make up the materials we encounter, billions of galaxies beyond the limits of our vision, the ultrasonic chirps used by bats to navigate, viruses, DNA, antibodies, aerosol droplets, and much more of reality as it is.

We typically experience reality through our perceptions of it, however our perceptions often distort reality, usually without us knowing it. For example, in the checker shadow illusion, shown below, two identically colored squares labeled “A” and “B” appear to be very different shades of gray. Reality as we perceive it may not be reality as it is.

We typically use words to represent our perceptions of reality. Words are one type of symbol used to represent reality. Other symbols might include sounds, hand gestures, icons, logos, drawings, models, analogies, and other representations. The mapping from words to perceptions to reality is often imprecise. We may describe a certain color simply as red, without clarifying what shade of red we are describing. If I tell you I am sitting in a chair, you might imagine a rocking chair, a desk chair, or a recliner. Syntactic ambiguity often adds to the confusion. The map is not the territory. Although most of us are familiar with the word virus, few of us can explain in much detail what a virus is.

People interpret observations to resolve ambiguity, increase certainty, and to account for the observations within some familiar model or analogy. As an example, please observe, and then interpret the image shown below.

What do you see? What else do you see? How certain are you of your conclusion? What do you have at stake in defending your interpretation?

Most people will see either a rabbit or a duck. If you see a rabbit, look again, and try to see a duck. Similarly, if you see a duck, look again, and try to see a rabbit.

This image, called the rabbit-duck illusion is inherently ambiguous. Someone who interprets it as representing a duck has as valid a claim to accuracy as someone who interprets this as representing a rabbit. In fact, it is neither and both. It is an ambiguous image open to at least two different yet equally valid interpretations. Similarly, a glass that is half empty is also half full.

This simple image allows for two different, yet equally correct interpretations. Life is often more complicated than ducks and rabbits, and we can reasonably differ in interpreting many words.

How do we interpret information about the virus that causes COVID-19? Each of us has a different understanding of what a virus is. Some may recall that colds and influenzas are caused by viruses, and these diseases are common and annoying, but rarely fatal. Others may fear outbreaks of deadly diseases caused by viruses such as Ebola and AIDS. Popular disaster films such as Outbreak and Contagion dramatize the consequences of novel viral infections. All of this is true, but how dangerous is it; what risk does the virus represent? As a result of partial information, rumors, varied experiences, and a range of risk tolerances each of us interprets the risk due to a virus differently.

Similarly, we also hold different understandings of what a vaccine is. Some remember the transformative effects of the polio vaccine, others may remember the 1977 suspension of the swine flu vaccination program, and still others may still be reacting to disinformation alleging a connection between vaccines and autism. Do you interpret a vaccine as lifesaving, or dangerous? Why? How do you know? How sure are you? What is at stake?

And then there are face masks. Because few of us have significant first-hand evidence that masks provide protection, and each of us is annoyed by wearing them, we interpret a mask as either prudent protection, or a mandated nuisance. Each of us can cite some reference or anecdote to support our chosen position. Some of us demand freedom from masks, while ignoring the fact that our freedom ends where others’ freedom begins, that masks protect others, and wearing masks is likely to shorten the duration of the pandemic.

Humans enjoy telling and retelling stories. Myths have been a part of human culture at least as long as recorded history. Folklore, oral histories, epics, origin stories, campfire stories, fairy tales, legends, bedtime stories, songs, poems, and soap operas are told and retold. Stories provide a memorable, coherent, compelling, and plausible explanation for events. They are also often fanciful and factually unfounded.

Several grand narratives currently divide our worldviews and political discourse in the United States. Conservatives often agree with Ronald Regan that “Government is the Problem”, while progressives tend to believe that “Government is the solution”. Each tribe can cite many examples bolstering their position. Beginning with their chosen narrative, conservatives often oppose mask mandates, while progressives scold the unmasked for endangering others and prolonging the pandemic. These arguments begin with narratives and extend to interpretations and symbols but are rarely based on a careful evaluation of evidence.

We are divided by several such narratives. More guns make us safer, or they cause needless violence. Climate change is the biggest threat to our future or is simply a hoax. Abortion murders babies or protects a women’s right to choose. God created man, or man created God. Capitalism is the solution or capitalism is the problem. Do you believe the experts or do you believe your friends? Various conspiracy theories provide especially troublesome narratives. Ideologies amplify cognitive biases.

The next time you find yourself in a contentious discussion, notice if you are talking about narratives, interpretations, symbols, perceptions, or reality. To find common ground and move toward some resolution of the conflict, lead the discussion away from the narratives and interpretations and toward reality. Because reality is our common ground, this may be the most effective path toward that common ground.

Although the stories we tell about contentious issues are often very different, it is important to recognize that the underlying reality is the same for all of us. Work toward understanding reality and seek common ground.

Escape ideology, embrace ambiguity, investigate more carefully, and align your worldview with reality.

An extended exploration of these ideas is now available on Wikiversity.

Leland, the diagram of abstractions reminds me of the "pyramid of belief" in Dave Gray's book Liminal Thinking http://liminalthinking.com He says that our opinions are based on our beliefs, which are based on our conclusions, which are based on our assumptions, which are based on our relevant needs, which are based on what we observe and experience. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2G_h4mnAMJg